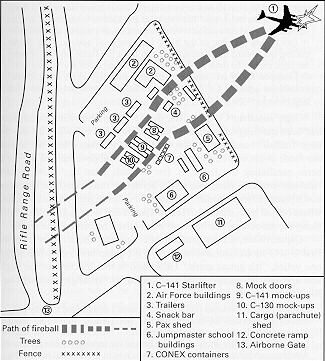

On March 23rd of 1994, a terrible mid-air collision took place between an Air Force F-16 and C-130 on final approach to a runway at Pope Air Force Base near Fayetteville, North Carolina. The F-16 pilot and his passenger ejected safely, but the F-16 crashed into the adjacent aircraft parking ramp and collided with a parked C-141. This collision caused a huge fireball which traveled along with the remnants of the F-16 to end of the ramp where 500 army paratroopers were staging for a practice para drop. Twenty four paratroopers eventually died and over eighty were injured. The damaged C-130 landed safely. The disaster made national news and was recognized by President Clinton who visited the disaster site two days later. I was involved with both the original accident investigation and a re-investigation conducted a few years later. (Green Ramp Disaster on Wikipedia)

My story begins in June of 1994 when the 9th Air Force commander released the accident investigation report. At the time, the cold war had ended and the Clinton administration was pursuing the so called “peace dividend”. Vice President Gore was in charge of the “Re-inventing Government” program which was reducing the defense budget. The Pentagon was downsizing and closing bases as a consequence. A base closure is a highly charged political process. No congressman wants a military base to close in his or her district. These base closings resulted in forced dissimilar aircraft operations at the remaining bases and the creation of a new organization called a composite wing. A composite wing was in place at Pope Air Force Base on the fateful day of the accident.

Dissimilar aircraft operations put aircraft with different operating characteristics like that of an F-16 and C-130 in the landing pattern of the runway at the same time. This makes the air traffic control climate much more complex which increases risk. Certain politicians seized on this issue as a way to impede a base closure. The Armed Services Committees of both houses of Congress requested the investigating officer of the Pope accident appear to explain his report.

Like so often happened while serving on the air staff in the Pentagon, I was working at my desk one morning when out of the blue I was called to the head office (AF/XOO) to review the Pope accident report and then accompany the investigating officer to the Hill for committee hearings on the accident. I had never seen the report before and only had one hour to review the one inch thick document. I read the executive summary and conclusions and then closely read the attached control tower audio tape transcript. I had insufficient time to review the full report.

I finished my review and learned I would be the only air traffic control expert on the briefing team. The tape transcript did give me an overview of what had transpired in the control tower at the time of the accident. There was no doubt in my mind that the Pope control tower had failed in its primary job of air safety by creating a confusing environment in the landing pattern. I noted the report had also completely exonerated the F-16 pilot.

During good weather conditions, as was the case on the day of the accident at Pope, the control tower sets up the landing sequence of arriving aircraft (who’s first and who’s second etc..) and advises pilots where other aircraft are in the pattern. It’s the pilot’s responsibility to separate his or her aircraft from other aircraft in the pattern by visual means. The F16 pilot had been advised by the tower of the C-130 in front of him on final approach and proceeded ahead until colliding with the C-130. This fact stuck out in my mind. But I hadn’t had time to adequately review the report to be sure there weren’t extenuating circumstances mitigating the pilot’s decision to proceed.

I met the investigation officer, Colonel Vincent J. Santillo. Jr., an F-16 pilot, as well as other members of the team. We proceeded to Capitol Hill to brief the House and Senate Armed Services committees. Colonel Santillo briefed the House first with the team sitting behind him. During this first briefing, he made factual errors concerning internal control tower procedures. As we walked to the Senate committee room for the next briefing, I advised him of his errors. I found it strange that he did not have an understanding of basic control tower operational procedures when he had cited the tower operators as the sole cause of the accident in the report.

Colonel Santillo finished the second briefing to the Senate. Based on the questions the committee members asked in both briefings, I realized they were not really interested the accident itself, but rather how it could be used to further political agendas. Walking outside, I was approached by the 9th Air Force Commander who had observed the briefings. The general asked me if I had any comments about the report and I replied that I hadn’t had enough time to review the report to be able to form any valid opinions. At the time, I found his question strange since the report had been approved by him before its publication. It was a little late to be asking a senior air traffic control officer his opinion about the report. As I was to find out later, his apparent misgivings were well founded. (Green Ramp Disaster Original and Follow-up Accident Report)

But that was not to be the end of it. The control tower watch supervisor on duty the day of the accident was forced to retrain and transferred to a menial job in base operations. He felt he was treated unfairly and that the F-16 pilot shared the blame, yet was exonerated. He filed a complaint with the Air Force Inspector General (IG) but the claim was dismissed. Not satisfied, he filed the claim with the Department of Defense Inspector General (DoD IG). The DoD IG, being in a position to be more objective, saw merit in the claim. He sent the accident report to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for an unbiased 3rd party assessment. The FAA reviewed the report and concluded the pilot was partially culpable and recommended a further look. Based on this, the DoD IG recommended a re-investigation to the Secretary of the Air Force, Dr. Sheila Widnall. She ordered the re-investigation. After more than two years of bureaucratic grinding, the re-investigation was to take place. (Associated Press article dated 18 January 1997)

By this time I had left the Air Staff and been reassigned to Nellis AFB in Las Vegas, Nevada, as the Operations Officer of the 57th Operations Support Squadron. I was at home one weekend in February, 1997 when I received a call from the Operations Group Commander, Colonel “Hime” Oram. He told me that I had been tasked by the commander of Air Combat Command to join a team re-investigating the Pope accident. I wondered who had recommended me for this accident board. While on the Air Staff, I had met Dr. Widnall, the Secretrary of the Air Force. I had also worked with the DoD IG on several occasions. It also might have been someone from my old office.

At 10:00 Tuesday morning, 18 Feburary 1997, I left Las Vegas in my truck and headed for Davis Monthan AFB near Tucson, Arizona. I checked into the Davis Monthan Inn that night. The next morning the team assembled in a conference room for introductions. The team included an Air Force lawyer, a C-130 pilot, an F-16 pilot, a psychologist, and a human factors specialist from the Biomedical Service Corps. We were all seated around the conference room table and the investigating officer, Colonel Michael S. Brake introduced himself. And then something happened that I will never forget. He looked at me and with a touch of anger in his voice let me know he was not happy that I was on the team. I had never met him before so I was dumbfounded. Everyone in the room had a “what just happened” look on their faces.

Throughout my time as an Air Force air traffic control officer, I had experienced this attitude in Air Force fighter pilots time and time again. The FAA entrusts stewardship of parts of the national airspace system to the military. In return, the military is required to follow the rules the FAA sets for all air traffic controllers. These rules put air safety paramount over all other considerations. The Air Force fighter pilot culture encouraged “pushing the envelope”. This created a natural conflict between fighter pilot and controller. To Colonel Brake, the re-investigation of the Pope accident was nothing more than an attempt to ruin the career of a good F-16 pilot. I believe he projected his contempt with air traffic control on me. Welcome to the team.

We spent a week in Tuscon going over the first accident report. Having more time to review the report this time around, something else stuck out in my mind. The investigating officer, Colonel Santillo, was the 6th Operations Group commander based at McDill AFB, Florida. When appointed as the investigation officer, he had taken two of his own air traffic control non-commissioned officers (NCOs) with him as his air traffic control advisors. Normally, accident investigation teams are made up of officers not NCOs. He must have known this accident investigation would put him in a position to judge controller and pilot actions. These NCOs were not going to tell him something he didn’t want to hear since they worked for him.

During this week, I kept quiet and did not offer any opinions which would have probably evoked another confrontation with Colonel Brake. Throughout my time in the Air Force, I had always enjoyed better interactions with airlift pilots. They seemed to better appreciate the job of air traffic controllers. Major Mitch Gerber, the team’s C-130 pilot, was no exception and we hit it off immediately. We spent time together and went on cross-country runs after work every day. He was down-to-earth and I liked him.

On February 25th, we left for the Tucson airport on our way to Fayetteville and eventually Pope AFB. We were able to keep our rooms back at Davis Montham while we simultaneously checked into billeting at Pope. This is the only time in my Air Force career that I was able to “double billet”, one of the perks of being on an accident investigation team. We checked into Pope billeting that night at 8:15.

At our first meeting at Pope the next day, Colonel Brake told me he had no interest in talking to the control tower watch supervisor who had caused this re-investigation and was still working at Pope in base operations. Our purpose at Pope was to simply re-create the accident. The flight recorder of the F-16 had been destroyed in the crash and the C-130 flight recorder had malfunctioned. Colonel Brake would fly the same pattern the accident F-16 had flown with the same configuration and weather conditions. At a different time, a local C-130 pilot would do the same. We would take this newly captured data and re-create the accident in a computer simulation with the original control tower audio tape recordings providing the sound track.

On the day of the accident, the F-16 pilot was performing a maneuver called a simulated flameout (SFO) approach. This emergency F-16 approach has the pilot throttle back the single engine and glide to a landing from a high position near the runway. Since the approach was initiated outside the control tower airspace, Fayetteville Approach, an FAA radar facility, would have to give approval. A minor error made by the FAA the day of accident was cited in the original investigation report as a contributing factor. I would have to coordinate Colonel Brake’s planned SFO maneuver with them since they had prohibited SFOs at Pope after the accident.

I contacted the local air traffic control officer and he made an appointment that day with the FAA facility chief at Fayetteville Approach Control. We met with the facility chief and his assistant and I explained who I was and what we intended to do while at Pope. When he realized we intended to fly an SFO approach, the chief emphatically denied authorization. I was a little amused since he apparently did not realize the high level interest this accident re-investigation had. I was on a “mission from God”. I asked him if he was sure he wanted to deny the maneuver. He wouldn’t budge.

We went back to the air traffic control office at Pope. I still had contacts back in Washington DC from my time on the air staff. I called the Air Force liaison office located in the FAA headquarters building in Washington. I talked to a friend and explained the situation. She said she would take care of it. The next day, we got a call from the Fayetteville FAA facility chief who wanted to meet with us in his office. We met with the the FAA chief and his assistant once again. This time there was a huge change in attitude. They were falling all over themselves to help us get the SFO procedure done. We were able to complete both the C-130 and F-16 flights while we filmed them from the Pope control tower.

While we were at Pope, another deficiency from the original investigation became apparent. When the accident occurred, there were other C-130s in the vicinity of the airport whose crew members were witnesses to the catastrophe. The original investigator, Colonel Santillo, never interviewed these C-130 crew members. By now one had left the Air Force and was flying for a commercial airline. We were able to contact him between flights and interviewed him over the phone. One other C-130 crew member in the same plane as well as a crew member whose aircraft was on a nearby taxiway were also telephonically interviewed. But, none of these interviews added anything new to the investigation.

We successfully captured data from the flights of an F-16 and C-130. We also located the original control tower audio recordings and made copies as well as a written transcript. With data collection complete, our time at Pope ended. On 3 March, after spending a week at Pope, we flew back to Tuscon. We spent the night at Davis Montham and the next afternoon flew to Tinker AFB located in Oklahoma City.

For the next four days we used Tinker’s Mishap Analysis Animation Facility (MAAF) to re-create the accident in a computer animation. Combined with the control tower recordings, we were able to witness the whole accident in real time. Hearing the original control tower tape recordings gave me a new perspective on the attitude and state-of-mind of the F-16 pilot. He seemed to be overly relaxed in his communications with the tower almost to the point of being flippant. Putting all the pieces together, I was convinced he was partially responsible for the accident. The control tower had set the stage but had he acted in a careful manner, the accident might have been prevented. We flew back to Tucson on March 8th and spent the next 6 days at Davis Montham finishing up the analysis of the accident.

On the final day at Davis Montham, Colonel Brake had the whole board vote on the F-16 pilot’s culpability in the accident. The vote was unanimous in favor of the culpability of the F-16 pilot. I’m sure Colonel Brake wished otherwise, but the board consisted of pilots, controllers, and human factor specialists. He had no choice but to concede. Colonel Brake dismissed the board and proceeded to write the report alone. I drove back home to Las Vegas on 14 March.

In June of that year, the final report was released. (Associated Press Article in the Valdosta Daily Times (Georgia) dated 22 June 1997). Originally, the controllers involved in the crash were fined, demoted, and relieved of duty. And for all his trouble after the release of the second report, the watch supervisor who had made the DoD IG complaint was given an article 15 (non-judicial punishment). Three months later, on September 3rd, the F-16 pilot, Captain Joseph R. Jacyno, was promoted to Major (Congressional Record) and continued on flying status. As far as I know, no action was taken against Colonel Santillo, the original accident investigation officer, for his biased report.

The accident was a terrible event and like most accidents of this sort had multiple causes. The initial accident investigation and its follow-up investigation reaffirmed to me how corrupt the culture of the Air Force had become by the 1990’s. I have been retired now for over twenty years and this corruption was one of the many reasons I chose not to continue on in the Air Force at the 21 year point. As a lieutenant colonel, I could have stayed for 28 years. Some events which have taken place over the last twenty years have given me hope the culture has changed and the Air Force is a better functioning organization. But in this case, the corrupt fighter pilot culture successfully protected its own.

Epilogue:

Here’s a link to an article from the Fayetteville Observer published on 24 March, 2019 and re-printed by military.com which recounts the stories of the C-130 crew involved in the accident:

‘I Can Still Picture it:’ Pilots Recall Role in Green Ramp Disaster

Here’s a YouTube video describing the accident:

Mr. Hammon,

Firstly, let me say thank you for your service to this country, the USAF and your fellow airmen… I was stationed at PAFB (90-96) and was on the ground and witnissed the accident as it unfolded from the time the sound of the F-16’s engine roar (as I assume the pilot to full-throttle) as the crew ejected to seeing the plane hit the deck, the C-141 and the Army troops scattering (as best they could) on Green Ramp. Myself, and three members of my section (Fuel Cell, 23 MXS) were working on a F-16 external fuel tank. Our location was at the 23MXS External Tank Farm-Facility (bldg. number lost to me) and was on “loop road”, left side if you were driving from the direction of the six plane hangers towards the JSOC bldg. when this all tragically unfolded. My apologies for being so long-winded… We were litteraly parallel to the C-141 when it got nailed, approximately a few hundred yards, my best guess.

In any event, that initial report, for whatever reason DID NOT sit well with any of us who saw it and had to respond on-scene because of the F-16’s hydrazine tank… We weren’t trained or worked in ATC or trained pilots… But, the way it was laid out, pinning it on the ATC members just did not add up. I’m glad I found this article and damn glad there was a second look/ investigation. It’s sad it took two of them to set the record straight.

Facts and truth do matter… those lives lost and those altered forever because of that event demanded it.

Thank you.

Lonnie,

Thanks for your comment on my article. I want to recognize your service as well. Too many Americans now don’t appreciate the sacrifices military members make for the well being of our great country. With recruiting experiencing such large shortfalls, I worry about our future. My involvement with the first and second investigations seems like ancient history now. I’m glad I could help set the record straight in a small way.

Tim

Very much appreciate your doing this. We lost 9 from our platoon that day. 2/504. Real scars left on the survivors. Unfortunately, these types of investigations are all too common in the military. Thank you.